Custom Sheet Metal Fabricator’s Deep Roots Guide its Future

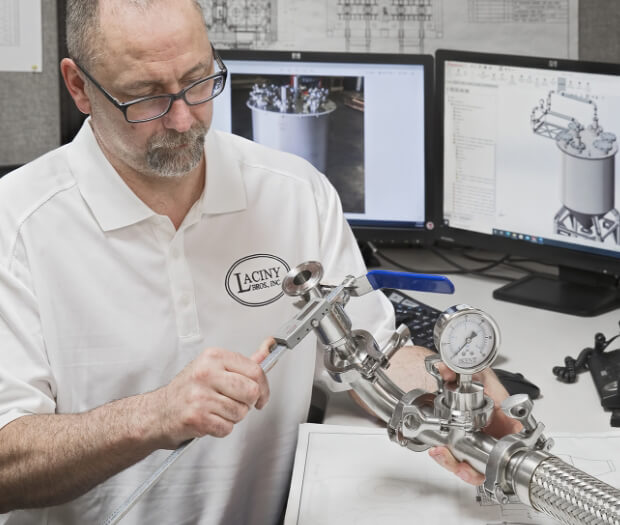

Rick Gratza, soft-spoken with a calm demeanor, never hurries a customer describing a problem and rarely says something just can’t be done. The challenge could involve thin sheet metal bumped to a smooth compound radius connected to other oddly shaped components, all polished to a mirror finish. It could be a precision-turned massive ball bearing destined for a brewery check valve or any number of other custom jobs that his employer, Laciny Bros., has been taking on for more than a century.

“Customers will call and say they need something done, and they don’t know how to do it,” Gratza said. “They need to get a project from A to B, and they don’t know how to get there. And that’s where we come in. We discuss their needs logically, and by the time we leave, they need to feel like they’ve gained something from the meeting. And they know that, yes, we’ve got this.”

Gratza, vice president of the St. Louis custom sheet metal and machine shop, returns to his office to think. He might talk with his shop supervisors, perhaps ask a brake operator about some unusual radius. They develop a plan, submit a bid, and quite often win the work.

It’s decidedly old-school and fitting for a 105-year-old shop. The original location, on 25th Street in St. Louis, had overhead shafts that powered belt-driven machines. The facility today, near the zoo in Forest Park (what was in 1916 the outskirts of town), has modern CNC equipment—a press brake, a waterjet with a beveling head, and various lathes and vertical and horizontal mills—so the technology isn’t old school. It’s more about the way people go about their work. No one works in isolation, and nearly everyone knows the basics of how things are made.

Many of the shop’s 32 employees have experience both in manual layout and software-based nesting, both turning hand cranks on a Bridgeport and machining a perfect piece the first time on a CNC mill. The culture spans between old and new and, as such, could be seen as a microcosm for manufacturing at large. The new—software, smart machines, unprecedented precision—has pushed manufacturing to new levels of productivity. But the old—human connections, common sense, creativity, collaboration—should never be forgotten.

Tools Guide Designs

Tim Laciny, company president and fourth-generation owner, described a common theme among younger engineers, most of them wizzes at SolidWorks. “I look at the design [in 3-D CAD] and say, ‘Well, that’s fine that you drew that on the computer screen. But do you have any idea how to make that?’ Then we take them onto the floor and show them our mills, our press brakes, our rollers, then tell them, ‘These tools should dictate your designs.’”

Laciny, 41, grew up amid years of transition in manufacturing. He recalled visiting the shop as a kid and seeing (at least from his perspective) big guys lifting large, heavy pieces of raw stock out of the racks and onto the layout tables. After a few hours sketching out complex mathematical equations to determine bend allowances and deductions for their flat patterns, these men would start punching, marking, and scribing complex trigonometry to make their parts.

“Minutes later they would be torching, cutting, shearing, bending, and rolling heavy metal into complex shapes and configurations,” Laciny recalled. “These were big, strong guys who could do very physical things, but they also had off-the-chart mechanical intellect.”

Gratza chimed in. “Before every job, you had to prepare, think, use math, and decide the tools ahead of time. That all took time, but it’s amazing the way we did things using the tools we had.”

Laciny described a job involving a large trough about 14 ft. long, 5 ft. wide, and 8 ft. tall, made out of various pieces of alloy 20 austenitic stainless steel, difficult to shape and weld. It was a re-order of a job placed in the early 1990s. To prepare a quote, Laciny dug through old files and came across the original job: no CAD file, just paper drawings and pages of layout and bend calculations made on loose-leaf paper. “I went off our old records to requote the job,” Laciny said, adjusting the labor rates and updating the material pricing. “When we won the job, I gave it to our engineer to put it in our CAD software and start ordering material. Well, the material quotes were coming in three times as much as what I had figured originally .”

“I went off our old records to requote the job,” Laciny said, adjusting the labor rates and updating the material pricing. “When we won the job, I gave it to our engineer to put it in our CAD software and start ordering material. Well, the material quotes were coming in three times as much as what I had figured originally .”

This was before the recent surge in material prices, and Laciny knew something had to be up. “I thought, ‘Oh my God, where did I screw up?’ But then I asked, ‘How did you get your material yield?’ And our engineer showed me how the software broke down the nest.’”

As it turned out, the software had split the nest into three different sheets. “When I went through our old files, I found out what our layout supervisor did. He fit it all on one sheet of alloy 20, and there wasn’t a spare inch left on that single piece. The computer needed three sheets to do it.”

Moreover, the computer was nesting for the company’s waterjet machine, something Laciny didn’t have in the early 1990s. Back then the entire nest was cut old-school, on a shear and using torches and hand-held cutoff wheels.

“Our layout supervisor at the time did it all in his head,” Laciny said. “And there were some complex rectangle-to-round transitions to be made. It wasn’t all straight 90-degree bends; these were all complex flat patterns. And alloy 20 is extremely expensive because of its corrosion resistance. You make one bad cut and you’re screwed. And these guys did it all on a gnat’s ass, no questions asked.”

In fact, the shop continued these old-school practices well into Laciny’s teenage years. “I remember watching those guys, how they’d shear it, lay it out with markers, swinging arcs, using angle finders. Watching those guys do all that was impressive as hell.”

Mechanical Art

The shop impressed Laciny so much that, as a recent high school graduate in 1997, he was ready to work. His dad, Bob Laciny, had a short stint at the local community college before he went right to work for the family business as a welder in 1972.

“Back then [in the early 1970s] it wasn’t looked down upon to become a welder or a machinist, carpenter, or plumber,” Laciny said. “It didn’t matter. You just found whatever steady job you could find to raise a family on, and it had no bearing on your intelligence or class. Out of all that, my dad grew a really nice business. He hired a lot of hard-working, intelligent people who didn’t have the exposure or means to go to college. But that didn’t mean they were uneducated or low class. The business grew substantially under my dad’s tenure, simply because he found a great group of intelligent people who loved working with their hands and making quality products.”

The teenage Laciny was fully aware of this. “I told him, ‘I just want to work here, and I don’t have to go to college for that. And you didn’t go to college.’ He said, ‘Yeah, I didn’t go to college, but you at least need a degree to fall back on. If anything happens with the family business, you need to have that education so you can do something else.’”

His father’s pragmatism came from years witnessing an industry changing with globalization. Tool and die shops in the area were closing. People were being laid off. What did the future hold?

For the young Laciny that future was college, but he didn’t major in engineering or any other technical field. After turning down a scholarship to the Chicago Art Institute, he enrolled at the University of Missouri and majored in interdisciplinary studies, including marketing, management, and sociology—three disciplines that, as other business leaders in metal fabrication could probably attest, have their use in the job shop.

Regardless, his artistic side never left him. “I enjoy creating mechanically. And I could carry that artistic side into the family business. We’re a custom job shop that makes one-off, unique projects, including complex machinery. We essentially make mechanical art.”

That artistic approach has guided Laciny’s management style and hiring strategy for the past decade. “I see this place as sort of a Six Flags for creative people who enjoy the challenge of making things from scratch. We look for people who might be bored or stuck in a rut where they’re at. Here, they get to be challenged, spread their wings, and be involved throughout the entire process.”

Laciny conceded that such an environment isn’t for everyone. If someone thrives on predictability and repetitive work, Laciny Bros. isn’t for them. “We’ve got a shop floor full of seasoned, versatile people. Our TIG welders don’t just weld. They assemble. They troubleshoot. They sometimes run the waterjet. They polish parts. We cross train as much as we can, and the more people learn, the more they’re paid. We don’t pigeonhole anybody.”

Laciny summed up his work philosophy this way: “If you don’t challenge yourself on a daily basis, you’re only as good as you were yesterday.”

Spreading Wings

Gratza, 60, will be retiring at the end of this year after 35 years with the company. He began as a machinist, working with a Bridgeport, a radial arm drill, a horizontal milling machine, and a small drill press—all while operating under the watchful eye of his supervisor, an ex-captain in the St. Louis police force. “He was extremely gruff, and he told it like it was.”

Gratza recalled the many times when his supervisor reviewed a setup, shook his head, and threw up his hands. “‘No, that’s not the way you do it!’ he’d say. He was extremely hands-on, and a pretty interesting old cuss.”

Laciny Bros.—and, one could argue, manufacturing overall—is not for the spineless.

Gratza worked as a machinist for five years before being promoted to supervisor. “And while I was doing that, I asked Bob [Tim Laciny’s dad] if I could learn some drafting and do a little design. He loved it when people took initiative.”

Gratza began as most designers and engineers did back then, by pushing lead, pencil on paper, at the drafting board. “The next thing you know, I learned AutoCAD. Then I eventually began shadowing Bob on customer calls where, again, I learned from the master. I learned how to treat our customers, to give them a sense of relief.” Tim Laciny doesn’t sugarcoat the shop’s challenges. The shop blends creativity with engineering and mechanical aptitude, and it’s hard to find someone with all three. At one end of the spectrum, engineering and technical school graduates tend to “overanalyze and overengineer everything,” Laciny said. “They rarely rely on common-sense instincts to solve problems.”

Tim Laciny doesn’t sugarcoat the shop’s challenges. The shop blends creativity with engineering and mechanical aptitude, and it’s hard to find someone with all three. At one end of the spectrum, engineering and technical school graduates tend to “overanalyze and overengineer everything,” Laciny said. “They rarely rely on common-sense instincts to solve problems.”

He added this stems in part from a severe lack of exposure to manufacturing—not equations or software, but where tools actually hit the metal. He recalled one recent intern he told to walk to the shop floor and talk to the lathe operator about a certain job. The intern gave a blank look. “He asked me, ‘What’s a lathe?’”

At the other end of the spectrum, hiring just anyone and starting from scratch doesn’t always work either. “If we take someone with no experience, no concept of basic mechanics or math skills, or no work ethic, well, you can only do so much with that too,” Laciny said.

Laciny conceded that, like most in manufacturing, he finds that hiring talent remains the company’s greatest challenge. He perhaps could take on higher-volume work and hire cheaper button-pushers, or dumb-down certain jobs to ease the cross-training expectations. But that would go against Laciny’s organizational philosophy, rooted deep in Eastern European sheet metal and machining craft. (Three Laciny brothers, all recent Eastern European immigrants, launched the shop in 1916.)

And so Laciny looks for the kind of person that has kept Laciny Bros. going for so long: the curious who take initiative and, as he put it, “aren’t afraid to spread their wings.”

The approach shaped Gratza’s career. Returning from a customer visit recently, Gratza sat in his office, looked at his notes, and spent a quiet moment. The customer was at a loss. Like many jobs Laciny Bros. quotes, there were no CAD files, not even paper drawings, just a problem in search of a solution. He perused the details, drew from years of shop experience, and began to formulate a plan. It was time to give the customer some relief. We’ve got this.

— Content and Image courtesy of Tim Heston, The FABRICATOR.